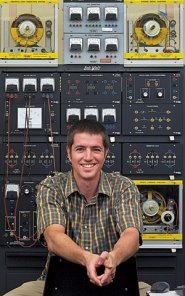

The Portland Tribune had a neat little article about Oregon Tech's Renewable Energy Systems degree last week. The RES major is very hot, attracting students from all over the USA. Bob Bass (right), the program director, is a key piece of the puzzle. The program currently is offered only in Portland but I hope we can bring it to the main campus in Klamath Falls someday or, as I discussed with some faculty today, have it as an emphasis within some of our already-established majors.

The Portland Tribune had a neat little article about Oregon Tech's Renewable Energy Systems degree last week. The RES major is very hot, attracting students from all over the USA. Bob Bass (right), the program director, is a key piece of the puzzle. The program currently is offered only in Portland but I hope we can bring it to the main campus in Klamath Falls someday or, as I discussed with some faculty today, have it as an emphasis within some of our already-established majors. OIT Degree Makes Pioneers of Students

Renewable energy program appears to be first of its kind

By Nevill Eschen

LocalNewsDaily.com Oct 7, 2006

Returning students to Oregon Institute of Technology’s Renewable Energy Systems program noticed this fall that their school is getting more crowded.

In the year and a half since the first students walked through the doors at OIT’s Southeast Portland campus, their numbers have multiplied almost nine times – to 44 who are enrolled for this school year.

They’re participating in a baccalaureate program that appears to be the first of its kind in the nation. Those who are leading the program are undaunted by being in the forefront.

“We have the resources and the brainpower here in the Pacific Northwest, we might as well develop them,” says Robert Bass, the program’s director and a recent transplant to the region.

The program has been in development for years, but recent events underscore its relevance: the rising price of oil, the volatility of many oil-producing regions, the popularity of hybrid cars, and the push for ethanol and wind power.

“We’re seeing a shift of how we view energy in this country,” Bass says, adding, “We can access resources close to home, avoid becoming entangled with regimes we’re not interested in.”

There is an urgent need to produce engineers who are schooled in solving energy problems in terms of renewable resources, according to the retired electronics department chairman who led the effort to develop the curriculum.

“We need a man-on-the moon, Manhattan Project” focus to marshal efforts toward renewable power, OIT professor emeritus John Yarbrough says.

One of a kind

OIT’s program draws students such as Adam Ward, who’s been working in his field of mechanical engineering for a decade. Ward, 32, decided after a “long career of making unnecessary things for cheaper” that wind power would be a worthy pursuit. Ward knew he’d need more training and searched the Internet to find it.

“OIT’s Web site came up. I just started reading about their program and it sounded like a lot of stuff I was interested in,” Ward says.

Bass, the program director, says that’s a typical path for many students. The magnitude of Yarbrough’s task of crafting the curriculum became apparent when he started looking for other renewable-energy undergraduate programs in the United States to use as a model for the coursework.

“I didn’t find anything here,” recalls Yarbrough, who shies away from the term “environmentalist” because it has political overtones, but is comfortable calling himself a “Teddy Roosevelt conservationist.”

He says there were undergraduate and advanced-degree courses, research and an option in energy – not necessarily renewable – at the University of Colorado’s physics program. But in terms of a bachelor’s degree, there was “nothing at the undergraduate level in any way shape or form,” Yarbrough says.

Yarbrough remembers thinking, “This is dumb, why aren’t they doing this?”

He expanded his search to the English-speaking world, finding that universities in Australia had what he was looking for.

The renewable energy systems degree is a three-year program; all entering students have at least their freshman year behind them. Because it’s OIT, the school leans toward boosting the firepower of its graduates by getting them on an engineering track.

The curriculum looks for all the world like the coursework for an engineering degree; it’s an intensive series that includes multivariable and vector calculus, electrochemistry and physics.

A long list of classesthat shape the renewable energy education includes electromechanical energy conversion, biofuels and photovoltaic systems.

It’s a priority for students to be able to communicate their ideas clearly, so writing and speech classes are part of the coursework.

Accreditation next step

Klamath Falls-based OIT has to call the program “renewable energy systems”; it cannot have the term “engineering” in the name because it’s not accredited as an engineering degree.

It lacks accreditation –essentially a seal of approval that it meets standards set by the profession – simply because it’s so new.

It would be impossible for any institution to launch an accredited program, since the school has to have graduated its first student before ABET, formerly known as the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology, will consider it.

ABET spokeswoman Liz Glazer says if accreditation is granted, it would apply retroactively to degrees granted for the program as approved, so that the first graduates who paved the way are not sacrificing their academic bona fides.

The program’s leaders are working to get it accredited. The steps include establishing an outside panel of people in the industry to ensure that students are getting an education that will qualify them as engineers.

A permanent panel will come later, but the interim industry advisory committee recent held its first meeting to get a briefing from Bass, Yarbrough and other program leaders.

“Initial reaction – it’s very rigorous, the rigor is there,” observes interim committee member Wayne Lei, Portland General Electric’s director of environmental affairs.

Lei says the engineering training will help students apply concepts up and down the chain of producing energy, including “newer types of energy.” And, he predicts, they’ll be employable.

“They’re going to be career-ready to really think about it. There should be a lot less on-the-job training,” Lei says.

Another interim council member, OIT graduate Jeffrey Kee, a professional land surveyor working for the Clackamas County Soil and Water Conservation District, was so happy to see his alma mater start the renewable energy systems degree that he made it his task to pull together the interim industry advisory committee.

“I think it’s great, because Oregon and Portland has been a hub of progressive ideas,” Kee says.

No comments:

Post a Comment